Art on a Heartland Farm

I’m proud to have done an art “thing” a few weeks ago in honor of Father’s Day.

On a hot afternoon in Iowa, with a sultry Midwestern thunderstorm on the horizon, I gingerly affixed a colorful, nine-foot-long welded Abstract Expressionist sculpture to the side of a weathered shed my grandfather built nearly a century ago.

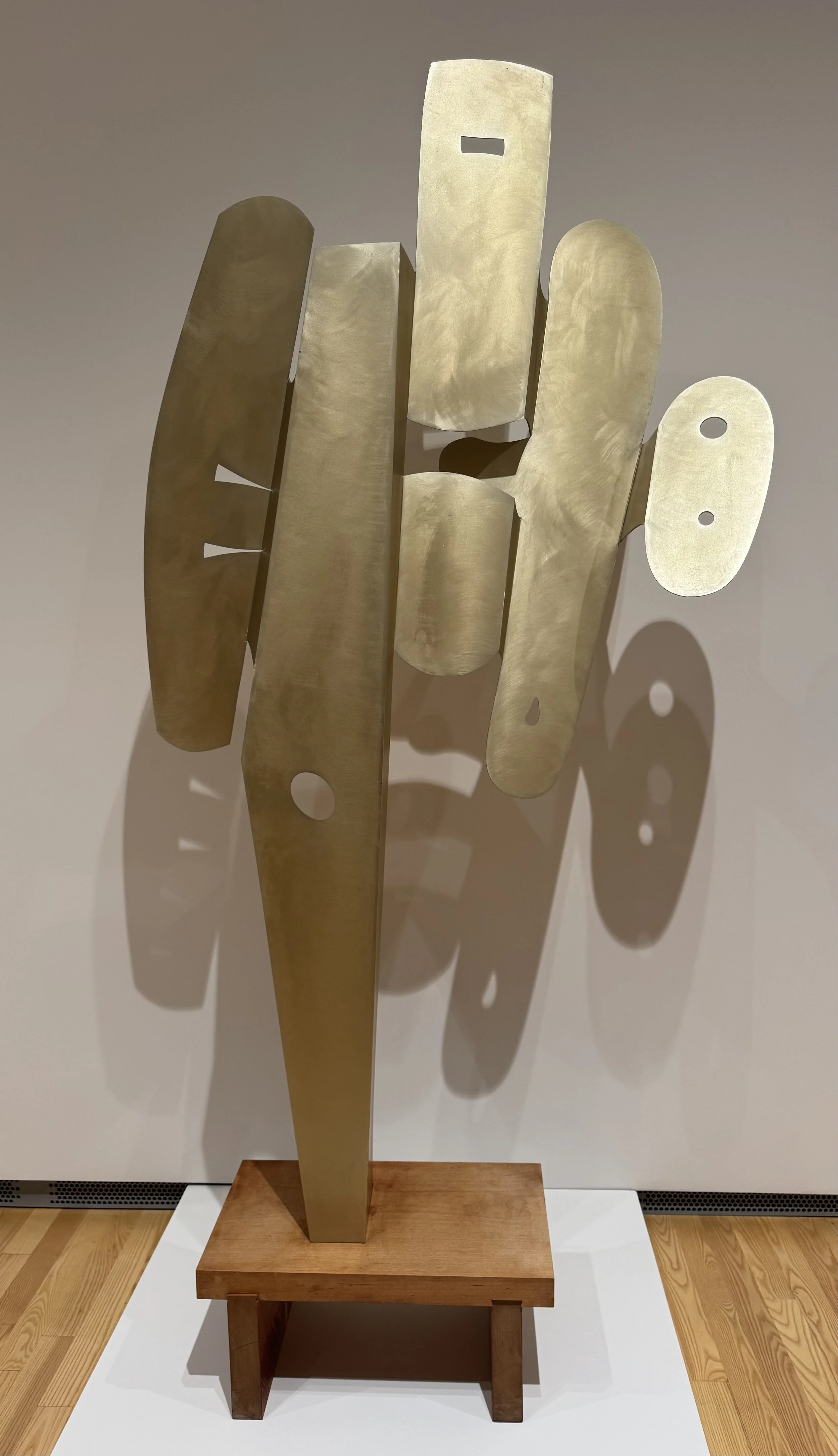

Views of Relief Sculpture (1985) by Abstract Expressionist sculptor David Hayes (1931-2013), generously loaned by his art foundation to the Blong Family Farm in St, Lucas, Iowa.

Although I’ve been back in Florida for days now, the profound awe engendered by activating this serene spot, located barely a stone’s throw from an old, weathered bridge that spans the gentle confluence of two creeks, has not yet begun to subside.

Loaned to my family by the late sculptor David Hayes’s son (a longtime friend and colleague), Relief Sculpture (1985) transplants notions of patrimony and play from one bucolic farm to another.

After all, Hayes himself was a father and grandfather, welding sculpture on a colonial-era farm in rural Connecticut for over 40 years of a career that earned him critical acclaim, among others, from MoMA, the Guggenheim, and the Rockefeller family.

Shortly after I hung Hayes’s sculpture on the Blong Family farm in St. Lucas, Iowa, (the tree in front of it the shed having been planted by my grandfather in the 1930s), a summer thunderstorm erupted, followed by a magnificent rainbow over the barn.

Not only that, but this abstract sculpture looks kind of like a fish, the perfect fit for our farm which gently hugs a local tributary known as the Bass Creek.

I love it so much. This is exactly what I strive for with every client: art that impacts deeply and joyfully.

Forging art experiences like this one into meaningful connections to place and patrimony lies at the core of Charting Transcendence’s art advisory practice.

Who Belongs to a Place? The Complexity of Indigeneity

Although my family has owned our farm on the Bass Creek in Iowa for over 100 years, archaeologists recently discovered indisputable evidence of settlement several thousand years old, showing that life was vibrant there long before the United States became a mighty agricultural and industrial nation.

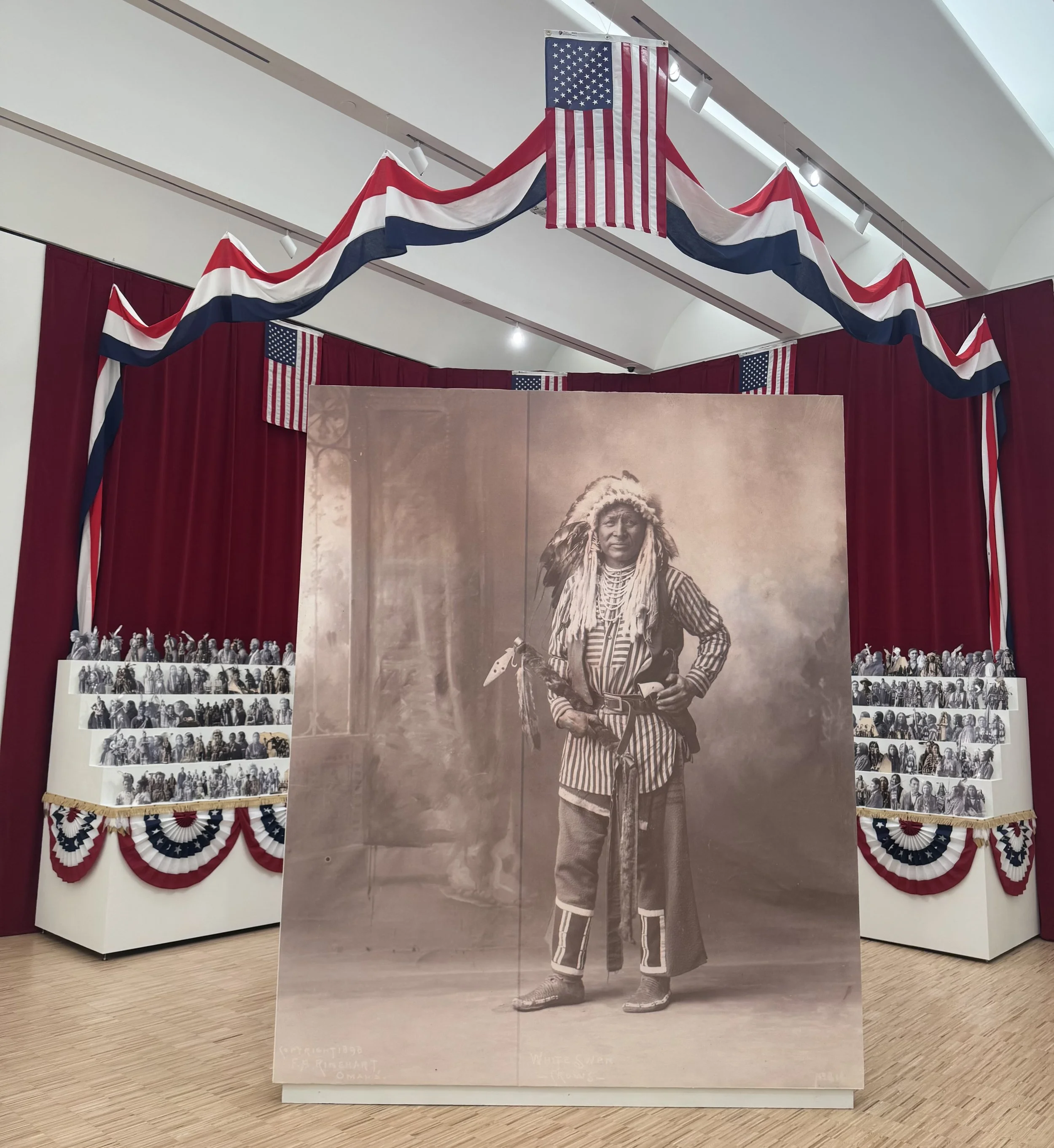

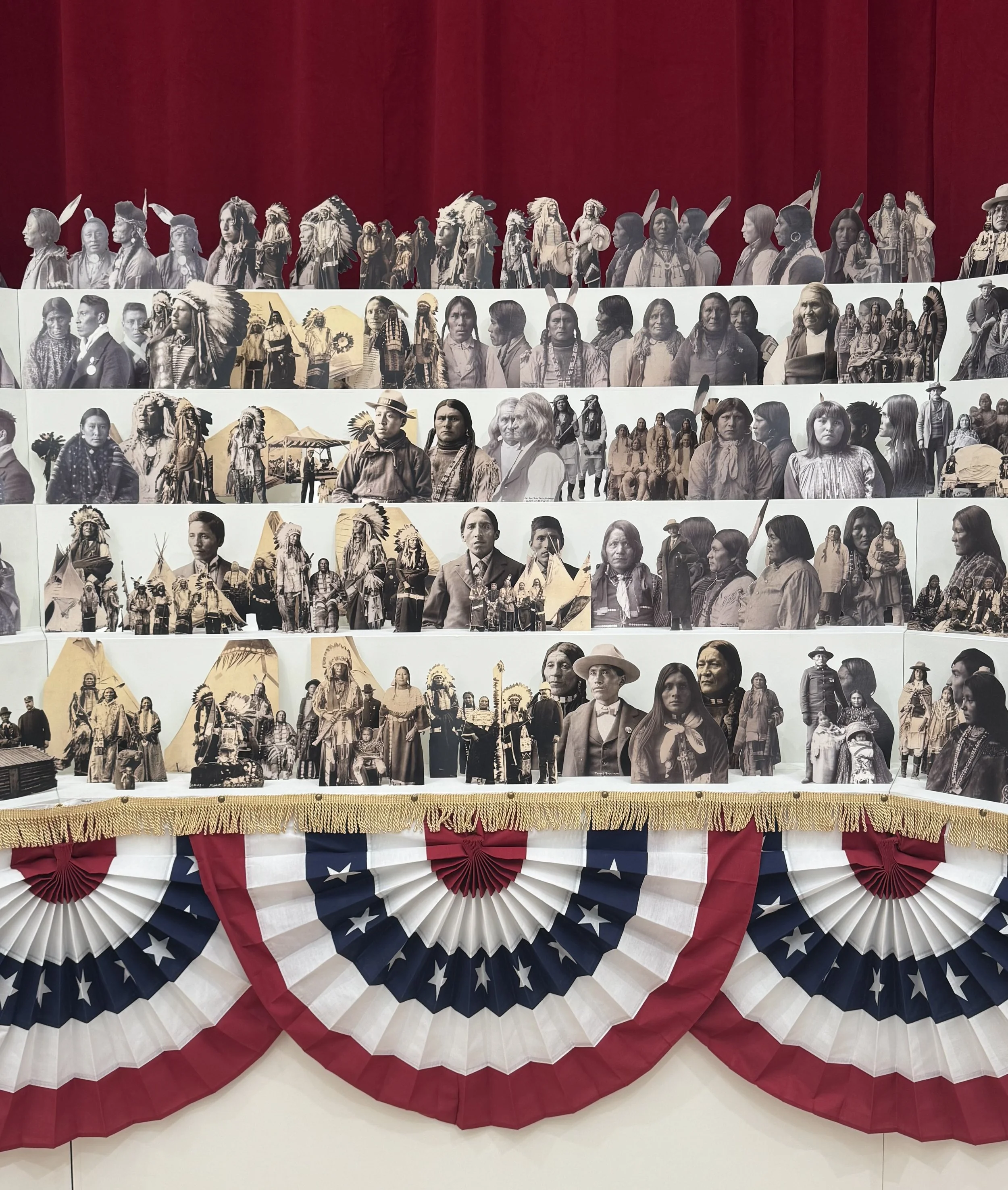

Wendy Red Star’s (b. 1981) The Indian Congress (2021/2024), a work that brings to light the largest ever gathering of American Indians to that date in Omaha in 1898.

As a member of the Apsáalooke (Crow) nation and a conceptual photographer, Wendy’s appropriation of historical photographs documenting recently subjugated Indian leaders speaks powerfully to the complexity of the indigenous experience in the USA.

Especially meaningful to me (personally) was the fact that The Indian Congress, which premiered in Los Angeles at The Broad in 2022, was recently purchased by Omaha’s Joslyn Art Museum in memory of a prominent Omahan I had once met, the father of my grad school classmate and friend.

Indeed, whenever I travel to look at art, I try to tune into a sense of indigeneity, a concept transcending borders and politics that embraces the understanding that people and artists flourished “here” long before “we” ever knew this place even existed.

This complexity is particularly apparent in art institutions across the Upper Midwest, where contemporary artists engage with histories of place and memory, tradition and sovereignty.

As I visited regional collections last month, I encountered powerful pieces of art, exploring themes of origin and displacement, by indigenous artists and others from around the world.

Raven Halfmoon (b. 1991), a citizen of the Caddo Nation of Oklahoma, works intimately with clay to make beautiful figurative sculptures. They now appear frequently in museum collections, such as at the Sheldon Museum of Art at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Minneapolis’s Dreamsong gallery is showing work by Julie Buffalohead (b. 1974), a member of the Ponca Tribe of Oklahoma. This essentialist feminist wall sculpture, Appearing (2025)

is made of rawhide, beads, dentalium shells and fabric.

Among my favorite artworks at the Minneapolis Institute of Art is the Gshrin Rje Mandala (1991), made by monks indigenous to Tibet. Sand mandala sculptures are, by definition, ephemeral, and so the Dalai Lama apparently had to provide special dispensation for this one to be preserved.

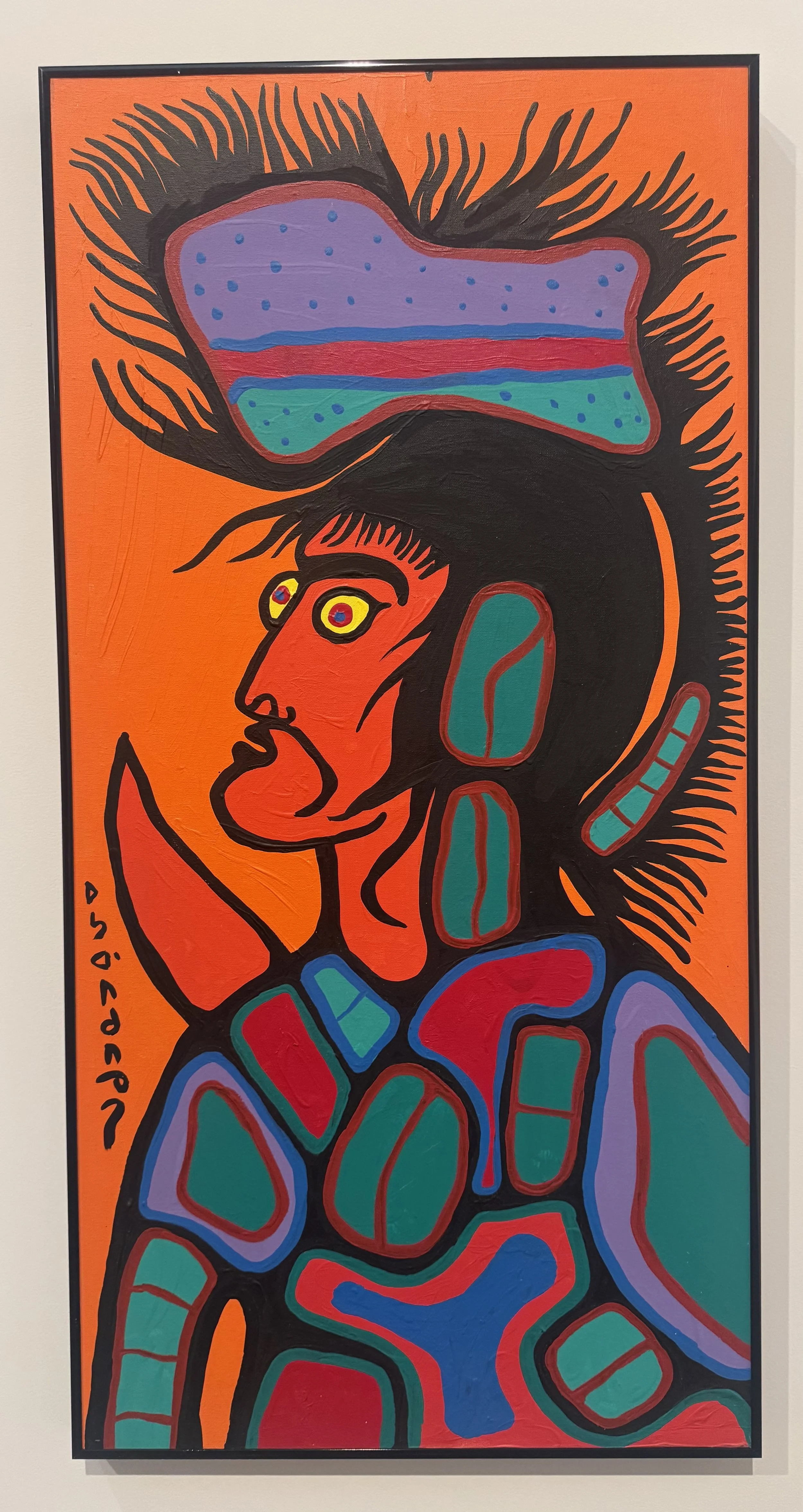

Davenport (Iowa)’s Figge Art Museum recently acquired Portrait of the Artist’s Friend (1992) by Norval Morriseau (1932-2007), a Canadian Anishinaabe self-taught artist whose work gained critical acclaim but also spawned the production of numerous forgeries, which plague the artist’s market until today.

Lakota artist Dyani White Hawk’s (b. 1979) Wopila | Lineage (2022), which was featured at the 2022 Whitney Biennial, is now in the collection of The Joslyn Art Museum in Omaha.

Tom Jones (b. 1964) is a Wisconsin-based Ho-Chunk photographer and artist known for his compelling visual narratives that explore Indigenous identity, history, and contemporary life. His work is included in this year’s Wisconsin Triennial at the Madison Museum of Contemporary Art.

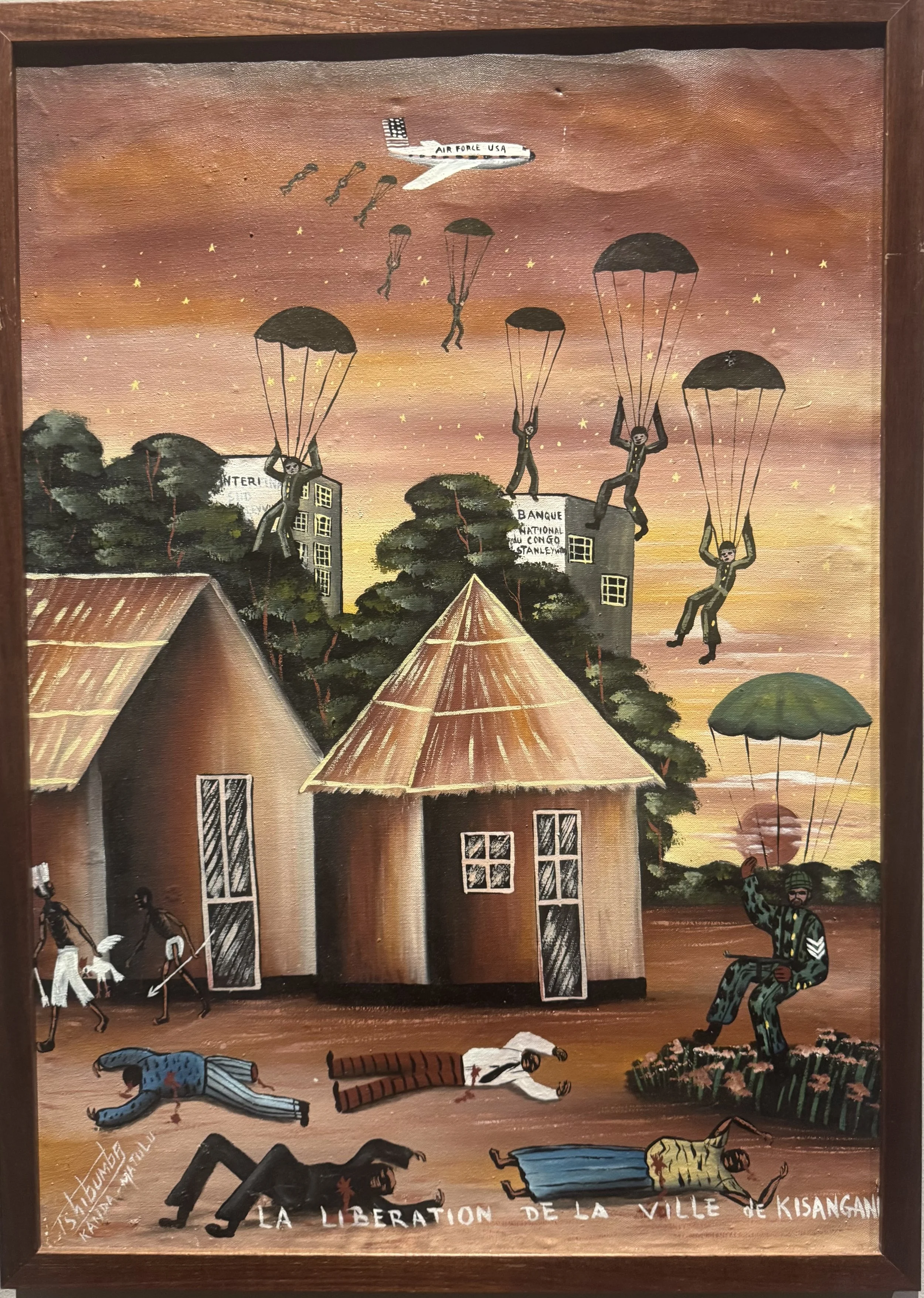

The Chazen Museum of Art at the University of Wisconsin-Madison is exhibiting Liberation of the Town of Kisangani (late 1960s-early 1970s) by Tshibumba Kanda Matulu (1947-ca. 1981) who depicted scenes from the early independence era of Zaire (now D.R. Congo), influencing contemporary Congolese artists. A former Belgian colony, Congo suffers from heavy, complicated post-colonial trauma.

A superstar indigenous artist for having represented in the USA at the Venice Biennale in 2024, Jeffrey Gibson’s (b. 1972) JUST LIKE YOU SAID IT WOULD BE (2019) is now in the collection of the Joslyn Art Museum. This beaded work incorporates not only geometric pattern and language, but also late 1980s music (as in the song by Sinead O’Connor).

Circling the Midwest in Search of Meaningful Art

The Western half of the USA is defined (and divided) by access (or lack thereof) to water, a fact realistically and sublimely exemplified by Pivot Irrigation #1, High Plains, Texas (2011) Edward Burtynsky (b. 1955) a photographer who specializes in abstract aerial landscapes. He recently closed a retrospective at the Minnesota Marine Art Museum in the Mississippi River town of Winona.

Over close to three weeks last month, I covered over 2,300 miles by car across Minnesota, Wisconsin, Iowa, and Nebraska. Seeking out art and architecture that speaks to the region’s spirit.

As always, the journey circled back to my family’s farm on the Bass Creek. Except this year something was different.

For each time I ventured out, waiting there on my arrival home, on the shed Grandpa Blong built, down by the old bridge, that beautiful David Hayes relief sculpture stood sentinel—a vibrant welcome and a reminder that even the widest explorations return to where meaning takes root.

Zig II (1961), a magnificent late sculpture by David Smith (1906-1965) in the collection of the Des Moines Art Center. Smith taught David Hayes (whose sculpture now hangs on the Blong Family Farm) how to weld at the University of Indiana in the mid-1950s.

The Sheldon Museum of Art at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln is an architectural gem, with a magnificent early 1960s building by Philip Johnson (1906-2005), who also designed part of today’s MoMA.

Czech-American artist Jan Matulka (1890-1972) channeled the European avant-garde in New York from the from the 1910s to 1930s, influencing American artists such as David Smith and Dorothy Dehner (1901-1994) at the Art Students’ League. Far ahead of his time, Matulka’s painting exhibited at The Joslyn in Omaha, Rodeo Rider, Santa Fe, (1917-1920), strikes one as more contemporary than its age.

Very volcanic over this green feather (2021) is an installation made up of 38 childhood drawings by Petrit Halilaj (b. 1986) that he made in a refugee camp in his native Kosovo during the former Yugoslavia’s 1990s-war era. It is currently on display at the outstanding Walker Art Center in Minneapolis.

Oozing with iconicity (and with just a single gray hair sticking out from the pompadour) this minimalist acrylic on burlap painting, Impersonator (2021), might be the best I have ever seen by Puerto Rican artist Jose Lerma (b. 1971) Wisconsin’s Madison MOCA is hosting an important museum retrospective of Lerma’s paintings, entitled Foreign in a Domestic Sense.

A typically flamboyant glass sculpture by Dale Chihuly (b. 1941), exhibited in the interior courtyard of the late 19th-century Italianate style Burlington Place, an office building constructed for one of Omaha’s many former railroads.

The outstanding International Quilt Museum in Lincoln, Nebraska, collects traditional and contemporary quilts from around the world. This one, Polyphonic 3, by Peggy Black, is stunning for its rigorous incorporation of color and form, reminiscent of Gee’s Bend quilting.

On a private tour of the Stanley Museum of Art at the University of Iowa, the director pointed out her favorite piece to me: Joy (1958), an anodized aluminum sculpture by Isamu Noguchi (1904-1988). Although considered “cheap” in the 1950s due to its use in household serving-ware, this industrial material has ended up aging well, lending a luminous softness to the work.

Digital Presence (1993), an acrylic on wood painting by Karl Wirsum (1939-2021), a favorite of Chicago collectors due to his affiliation with the Chicago Imagists, in the collection of the

Chazen Museum of Art at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Iowa’s Cedar Rapids Museum of Art, home to the largest collection of works by local artist Grant Wood (1891-1942) is housed in a quintessentially late-1980s postmodernist building incorporating the classical architectural forms seen in his paintings, especially American Gothic (1930), which belongs to the Art Institute of Chicago.

Hillside Theater Curtain (1956), designed by Frank Lloyd Wright (1867-1959), was executed in honor of his 89th birthday by his architecture students at his Taliesin studio in Spring Green, Wisconsin, Recently restored, it is a fascinatingly complex applied artwork.

The ultimate highlight of my 17-day trip to the Upper Midwest was my first live encounter with Tia Keobounpheng’s (b. 1977) Foundation No. 8 (2024) at the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul. It took the artist six months of drawing and scribbling by hand, with nothing but a protractor and hundreds of pencils, to create this 10’ x 20’ (3m x 6m) on wood.