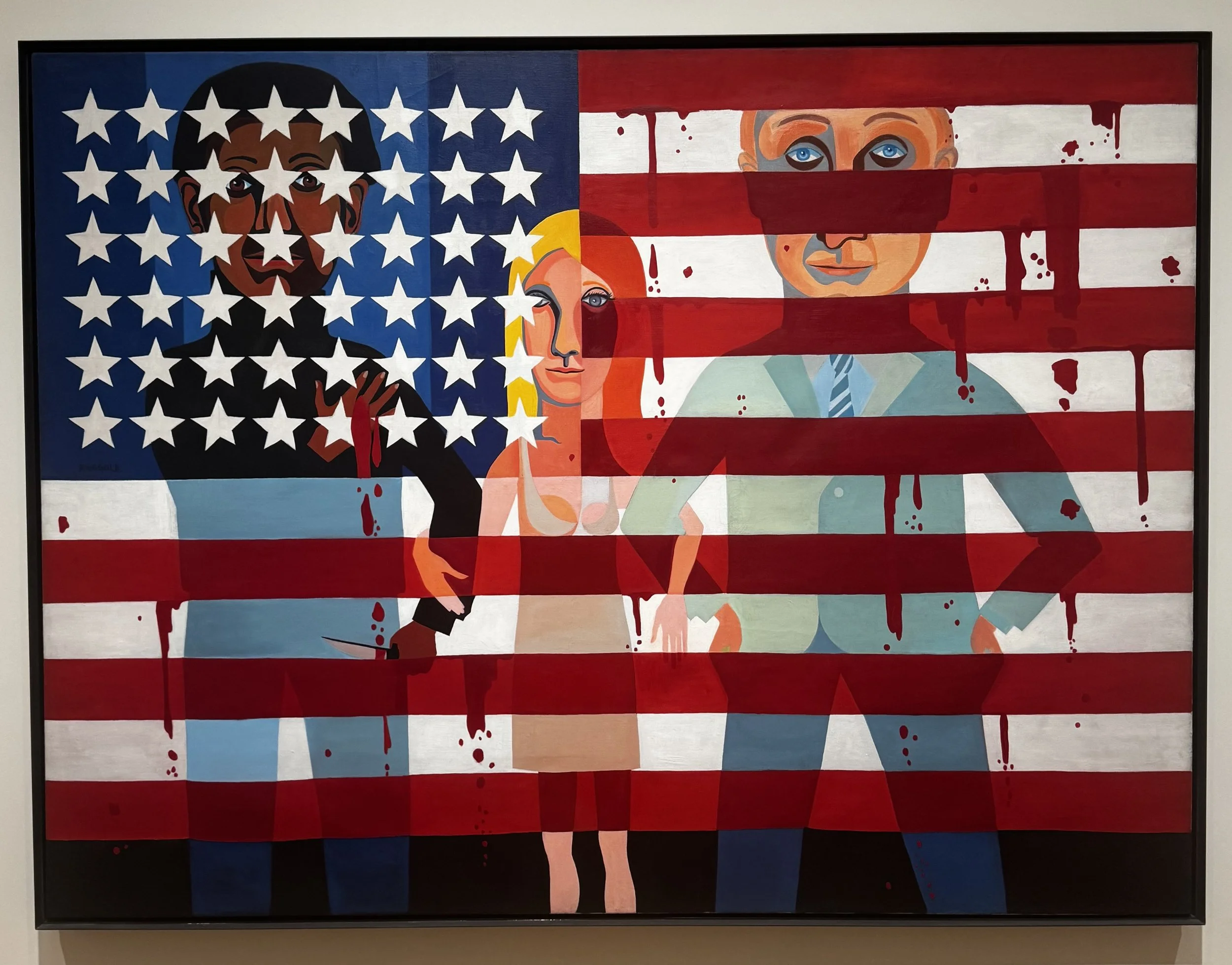

Art on the Fault Line of a Divided Nation

The American People Series #18: The Flag is Bleeding (1967), by Faith Ringgold (1930-2024), in the collection of the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. Created during an era of painful political and civic violence, Maryland’s Glenstone Foundation contributed the funds for its acquisition 2021.

Growing up near Washington, D.C. in the 1980s, I was obsessed for a time with everything about the American Civil War.

For my eighth birthday, I got an ice cream cake, and the lady at Carvel let me pick what I wanted on top from their catalog.

Uninterested in sports and not yet exposed to art, I did have a “thing” for history and underdogs, so my choice was simple: a Confederate flag.

A different era entirely, it would be years before I came to grasp the painful division conveyed by that symbol.

Tourists and protestors line Pennsylvania Avenue in front of the White House on September 30, 2025, one day before the current federal government shutdown.

Now older, wiser, and running this art advisory, I recently spent the last two weeks of September in my native mid-Atlantic region pondering the nation’s past and present political and cultural fault lines by engaging with modern and contemporary art.

Cities like Philadelphia, Baltimore and Washington boast magnificent collections spanning all centuries, many of them housed in neoclassical buildings, deliberate appealing to the admiration of the democratic ideals of Greece and Rome.

Meanwhile, America’s governing powers are now subjecting those buildings and much of the art they house to debate about what those ideals mean and to whom they apply.

Charting Transcendence maintains that the best art often reflects contrasts, contradictions, and tension in their conception and creation, not unlike those our nation has endured “in Order to form a more perfect Union.”

It is precisely this uncomfortable, essential work that the most compelling art undertakes, underscoring the forces of union and division that confront and conflict us in the world today.

Tradition & Discontent in the City of Brotherly Love

Philadelphia’s most famous resident is immortalized in this 1779 marble bust by French neoclassical sculptor Jean-Antoine Houdon (1741-1828) at the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

A city I hadn’t visited in years, a few days in Philadelphia reminded me of the revolutionary and reactionary traditions of the cradle of the Constitution, which is now the nation’s sixth largest city.

The Philadelphia Museum of Art embodies contrast this with a marvelous collection of work by the grandfather of conceptual art Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968), a curious and brilliant exception to an encyclopedic collection heavier on more traditional artworks.

The Barnes Foundation just down the Parkway sheds some light on this tension between rebellion and reaction. Over 100 years ago, local businessman Albert C. Barnes (1872-1951) assembled an eclectic collection spanning centuries, yet heavy on relatively newer work by French post-impressionists such as Renoir, presenting it publicly in a radically avant-garde way for its time.

Today, this collection worth upwards of $25 billion is virtually frozen in time, with a stipulation that the artwork never be sold or even hung in any other arrangement. It is a time capsule of one man’s efforts to redefine society’s artistic tastes (which, to the chagrin of early 20th century Philadelphians, Barnes successfully did).

A striking counterpoint to this is the newly opened Calder Gardens, dedicated to the joyful, inventive, abstractions of its native son, Alexander (1898-1976), America’s best known and most beloved sculptor of the twentieth century.

Apart from being transplanted to a new building in 2012, every piece of art in Philadelphia’s Barnes Foundation has remained static since 1951. Barnes’ choice of curating work by Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919) together with Old Masters and various metal oddities was considered unorthodox at the time but is now a major “brag” and tourist attraction for the city.

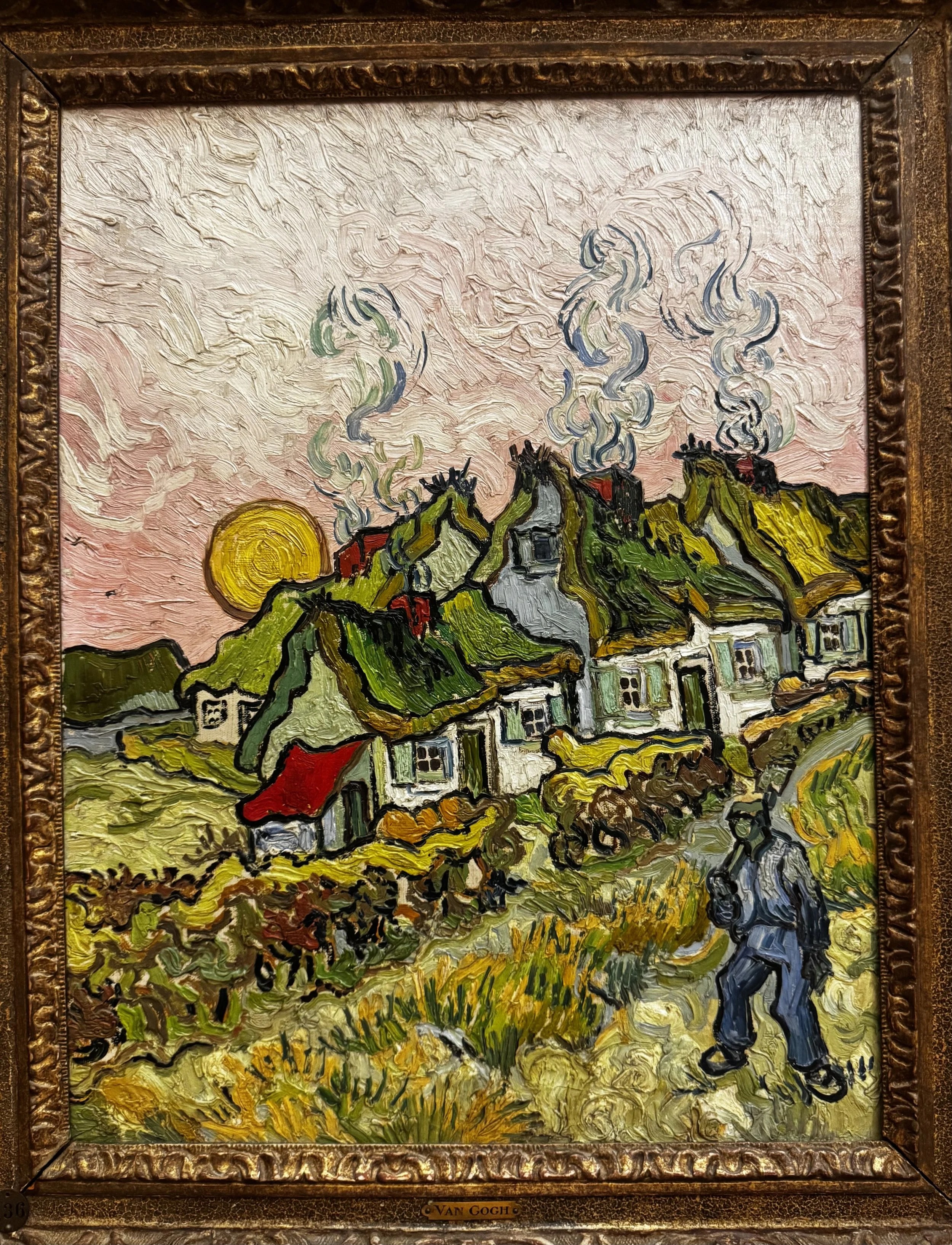

It is difficult to understand how far out of the mainstream an artwork like Houses and Figure (1890), an exquisite painting by Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890) in the collection of the Barnes Foundation, was at the time of its creation. In fact, it took several decades or more for Van Gogh to gain his reputation as one of the greatest painters of all time.

Two absolute masterpieces of late 19th-century French art by Georges Seurat (1959-1891) and Paul Cézanne (1839-1906) in the collection of the Barnes Foundation. Although neither could ever conceivably be sold, each is likely worth upwards of $100 million.

Swiss superstar architects Herzog & de Meuron, renowned for their innovative and context-sensitive projects and museum buildings, designed the Calder Gardens, Philadelphia’s newest art museum which opened in September 2025.

Calder, born in Philadelphia, was also a prolific painter and creator of other art media, including tapestries and jewelry, much of which shows the influence the European avant-garde had on his practice.

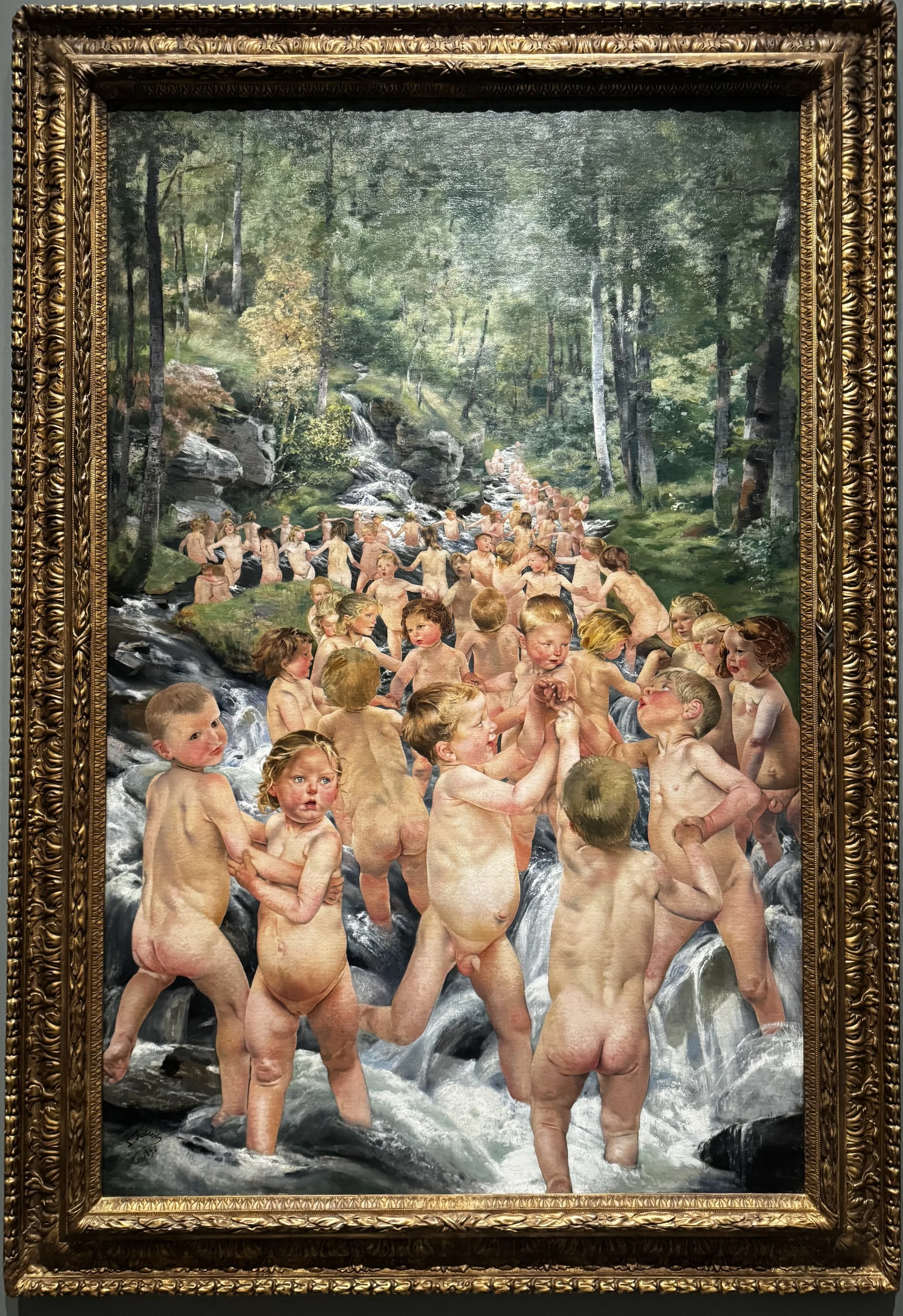

The Source of Life (1890) an unusual painting combining classical and modern styles by Belgian painter Léon Frédéric (1856-1940), was on loan from a family trust to the Philadelphia Museum of Art during my visit in late September 2025.

Jamie Wyeth (b. 1946) is a veteran realist painter who followed in the footsteps of his father Andrew (1917-2009) and grandfather N.C. (1882-1945). Jamie’s life-size Portrait of a Pig (1970) a testament to his skill, is in the collection of the Brandywine Museum of Art in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania.

Featured in the 2024 Whitney Biennial, Jamaican-born Mavis Pusey (1928-2019) is being honored with her first retrospective at the Institute of Contemporary Art at the University of Pennsylvania. This painting, Re-Gentrification or Regeneration (1986) is notable for depicting an urban area in flux.

Reflecting Boldly and Contemplatively in the “Free State”

A 45-foot high totem by Ellsworth Kelly (1923-2015) towers over the Gallery Pond of Glenstone Museum in Potomac, Maryland.

South of the Mason-Dixon line, Maryland offers two powerful yet opposing models for a modern museum: one that engages directly with the world, and one that offers escape from it.

The Baltimore Museum of Art (BMA) is an institution unafraid of bold, contemporary statements. There I was fortunate to catch the final day of an exhibition called Black Earth Rising, in which artists of color address ecological and environmental issues.

What’s even bolder, the BMA will soon host Amy Sherald's (b. 1973) retrospective, American Sublime, after the artist canceled its presentation at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, withdrawing it in protest after being told her painting Trans Forming Liberty (2024), even though it had been previously shown at SFMoMA and the Whitney without controversy, might be removed to avoid provoking political leadership in Washington.

Then there is Glenstone. A singular museum that I wrote about earlier this year, it offers a completely different experience from that of nearly any museum: silence, open space, and a deliberate lack of didactic wall texts.

Tickets are limited and children under 12 are not allowed. This curatorial choice is a form of power, placing the burden of interpretation on the viewer, which can be liberating but also confusing and isolating, depending on how prepared one is to let the entire experience, a veritable Gesamtkunstwerk, sink in.

Even experienced museum goers can miss out on some real gems at Glenstone entirely without a guide, which is why Charting Transcendence will be leading tours there again in 2026.

Thanks to two Baltimorean women benefactors who were early supporters of the French artist Henri Matisse (1869-1954), the BMA is blessed with one of the finest collections anywhere of his paintings today.

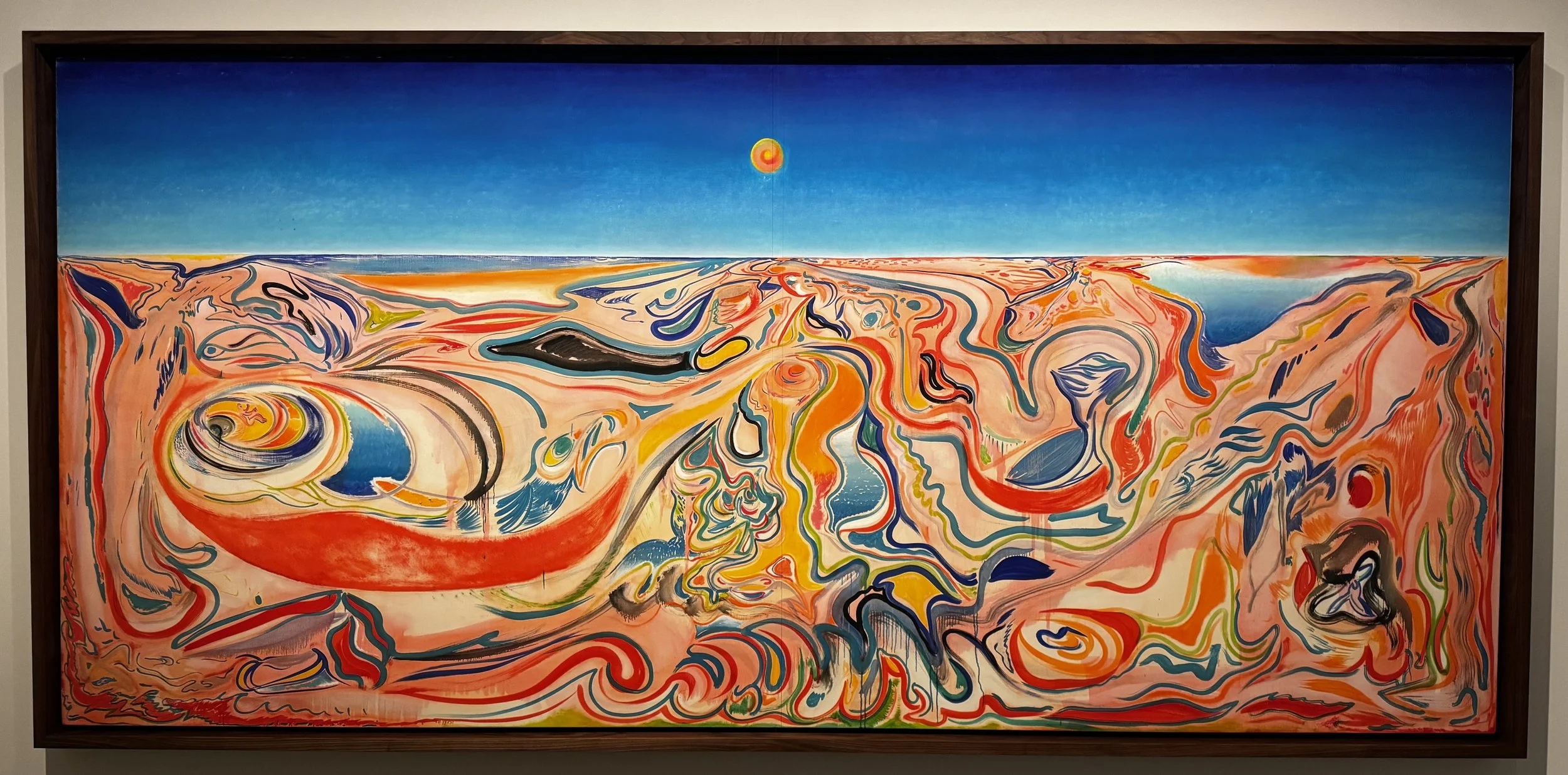

This nearly 12-foot-long (355 cm) canvas Viajando En La Franja Del Iris (2024) by Miami-based Cuban artist Alejandro Piñeiro Bello (b. 1990) was a central focus of the highly acclaimed Black Earth Rising at the BMA.

Out of a sense that freedom of landscape and the great outdoors do not apply to Black people like himself, Malcolm Peacock (b. 1994) created a redwood tree trunk covered not in bark but synthetic hair. Such bold installations are typical of the curation at the BMA.

Pink Tulip (1926) by Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986), one of a number of lovely modernist paintings in the collection of the BMA.

This 18,000-square-foot aquatic feature forms the heart of Glenstone Museum and is visible from a surrounding glass corridor connecting its galleries. It is both an aesthetic marvel and an ecological system, using harvested rainwater and natural filtration to support its seasonally changing plant life.

Richard Serra (1938-2024), Four Rounds: Equal Weight, Unequal Measure (2017), a massive, forged steel sculpture on display in its own freestanding custom gallery at Glenstone.

Clay Houses (Boulder-Room-Holes) (2006), constructed out of mud and stone sources from the grounds of Glenstone, by British land art master Andy Goldsworthy (b. 1956).

Satellite (2022), a large sculpture by African-American artist Simone Leigh (b. 1967) that fuses the female form with structural elements in bronze to explore complex themes, on the grounds of Glenstone.

Glancing Backwards & Forwards Across the Potomac River

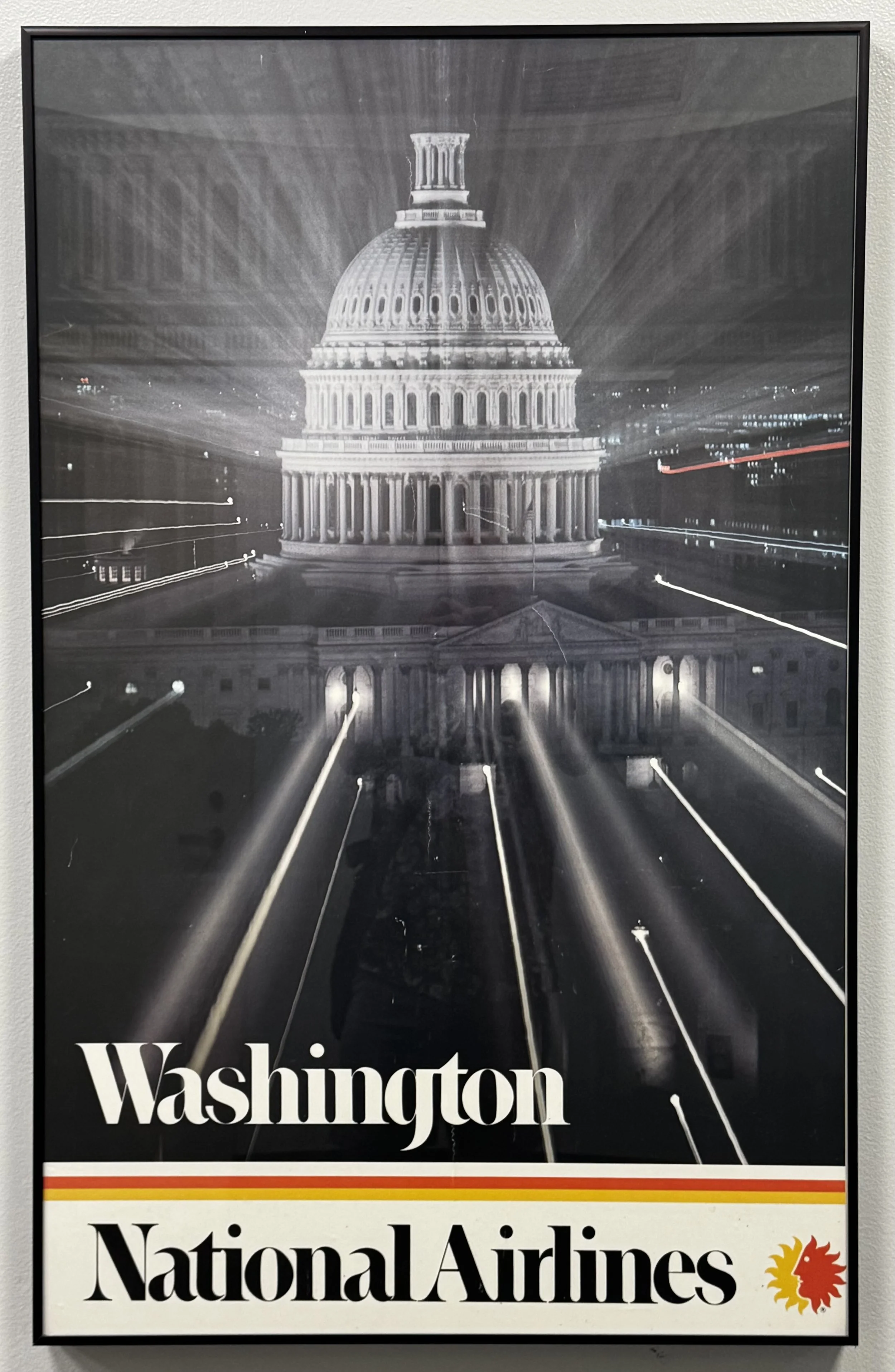

A vintage yet futuristic poster advertising Washington as one of the many destinations of the long defunct, Miami-based National Airlines, on display at Washington Reagan National Airport.

In Washington, D.C., the nation's museums, tasked with defending the very narrative of American art, have become the latest front in the culture wars.

Amidst headlines about federal overhauls of museum collections to eliminate so-called "divisive concepts," there is a palpable tension between the past and the future of American identity.

Yet a note of hope remains. In spite of politics, D.C.’s institutions remain on a forward-leaning posture, using wall texts and displays to tell a complex, inclusive story of American art (at least for now).

After all, to be American is to contain multitudes, a powerful, essential statement for a capital city built on a political fault line.

Loaned by hedge fund manager Ken Griffin for the Hirshhorn’s Basquiat × Banksy exhibition, Boy and Dog in a Johnnypump (1982) by Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988) is one of the artists very best and most monumental paintings.

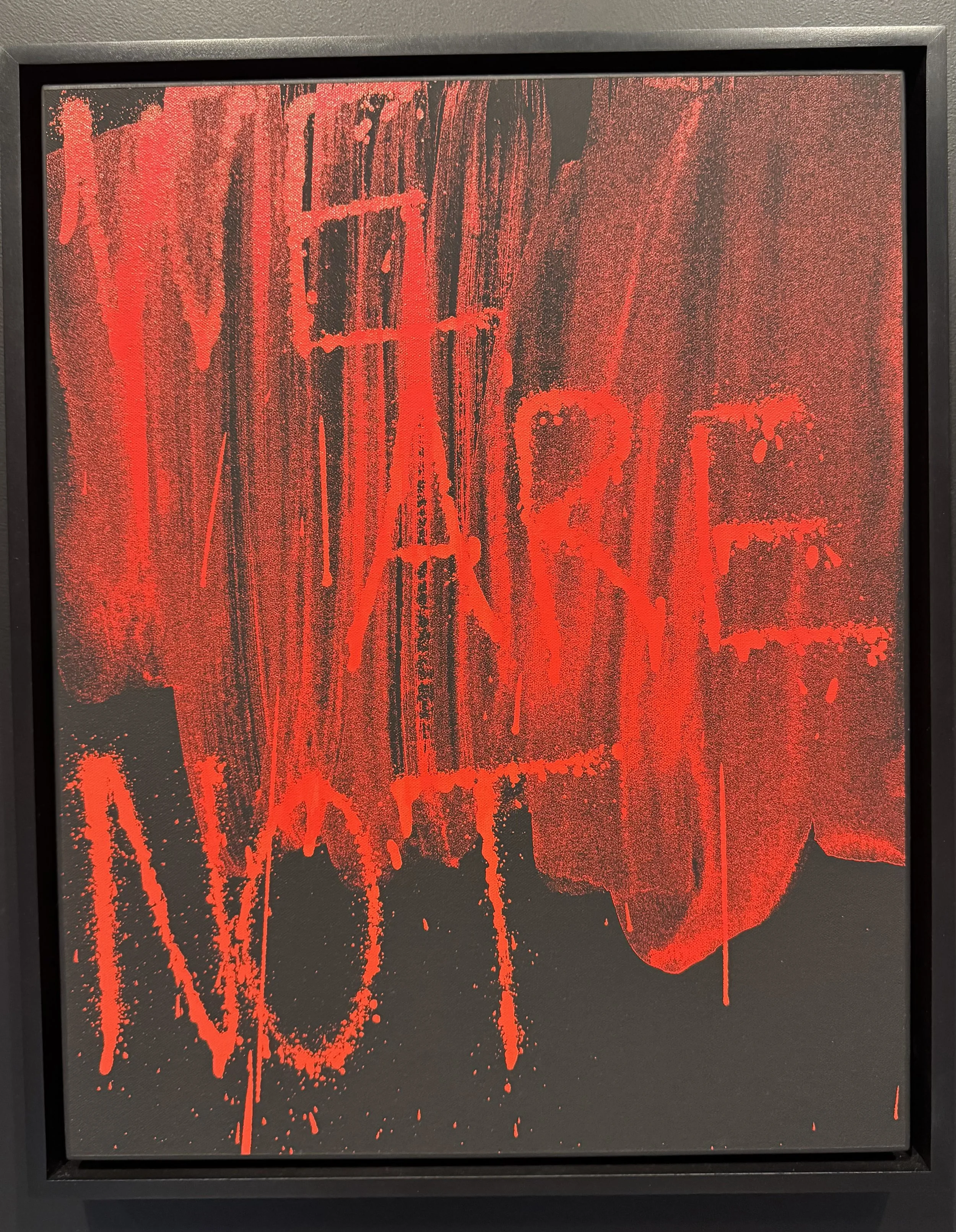

Adam Pendelton’s (b. 1984) retrospective at the Hirschhorn Love, Queen blends abstract painting with language and a conceptual approach that challenges the viewer’s comprehension.

Joseph Hirshhorn (1899-1981), the benefactor of the National Museum of Modern Art that bears his name, included this stunning painting of the Eiffel Tower from a birds-eye view by French painter Robert Delaunay (1885-1941) in his bequest to the nation.

Known for its cutting-edge contemporary collection in Miami, The Rubell Museum has had an outpost in Washington since 2022. Currently on display there is this canvas by Lucy Dodd (b. 1981), covered in herbs, minerals, and squid ink among other unusual materials.

This sculpture by Puerto Rican artist Daniel Lind-Ramos (b. 1953) in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM) is made of materials washed up on shore after the devasting Category 5 Hurricane Maria in 2017.

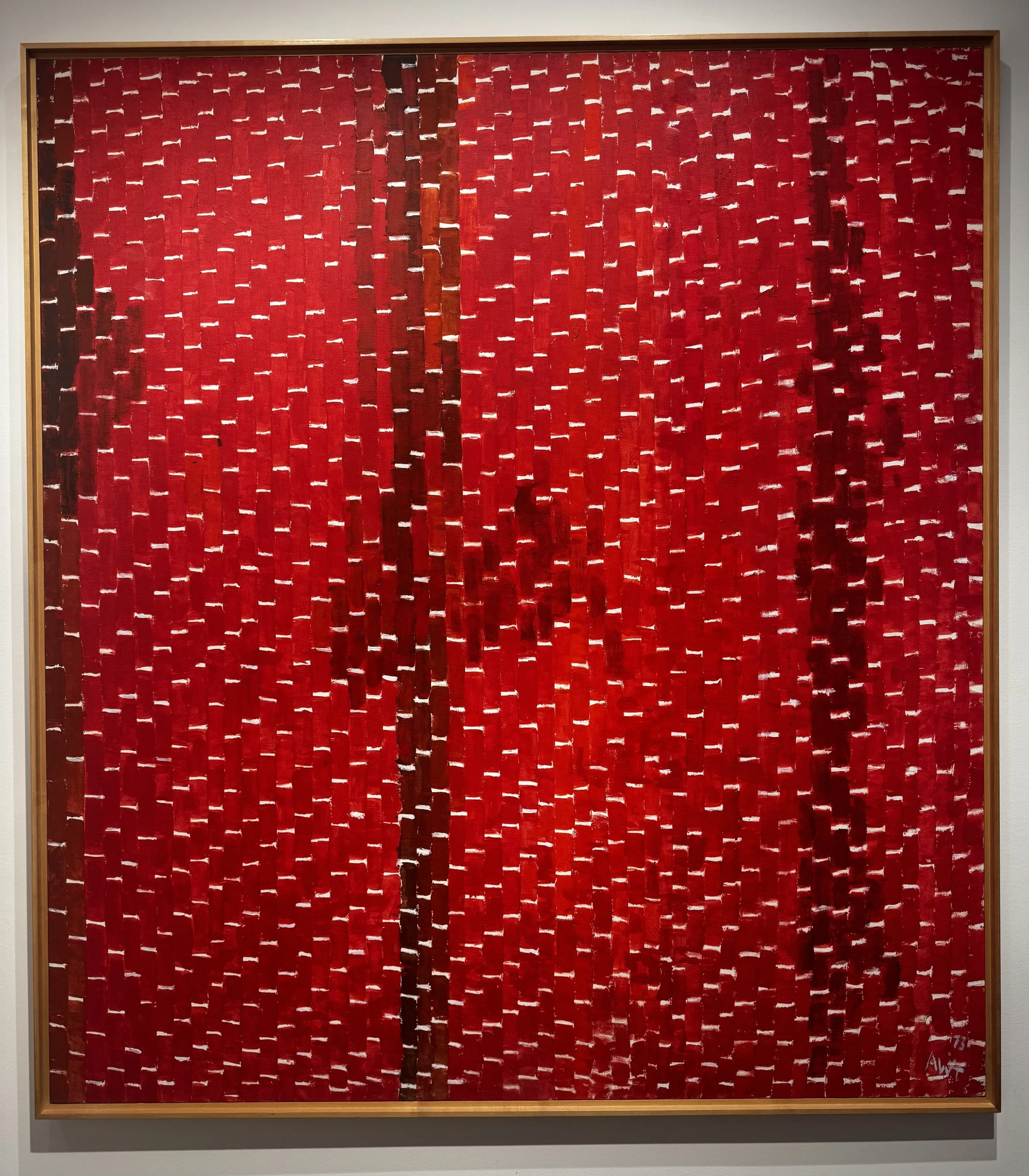

Alma Thomas (1891-1978) was a public-school teacher in the District of Columbia who late in her life painted color field abstract expressionist works like Orion (1973), now in the collection of the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington.

Recently acquired by SAAM, DNA Study Revisited (2022) by Roberto Lugo (b. 1981) is a urethane resin cast of his own body, painted in different patterns proportionate to his ethnic identity (Taino, Spanish, African and Portuguese).

Just as magnificent a work of art as every other mentioned in this newsletter, this Iowa State Fair Butter Cow in a custom refrigerated display case is the highlight of Washington, D.C.’s Renwick Gallery’s delightful exhibition State Fairs: Growing America’s Craft.