There’s Something About October

There’s something lovely about October (nothing to do with February, really) yet nevertheless has lately had me reflecting upon falling in love.

Whether you’re a die-hard baseball fan or just a guy running an art advisory in Miami, it’s a month when everyone has their eyes peeled for a change in season — and no one wants their heart broken.

Hank Willis Thomas (b. 1976) Love Over Rules (Horizon Blue), (2020), a neon sculpture on display recently at Jack Shainman Gallery in Tribeca, New York.

So now for my shameless plug: October is as good a time as any to consider engaging a guide to help you learn how to look for and fall in love with art.

Crafting a search for art around love and one’s own uniqueness, the most meaningful relationships that ensue grow out of a kind of courtship, cultivated, with intention and attention, over time. Not with a fleeting infatuation, but with a lasting connection that deepens with every encounter.

This is the journey that clients undertake with Charting Transcendence, a catalyst for looking longer, understanding more deeply, and seeing art not as a static object, but as a companion on an unfolding journey.

Alissa Alfonso (b. 1970) is a Miami-based artist who playfully repurposes discarded sports equipment and fabric into sculptures of plants and floral arrangements. Represented by Baker—Hall Gallery, Alissa has works available to collect from her current show that has just opened at the Miami Beach Botanical Gardens.

History, Luxury, and Personal Myth: The World of Justyna Kisielewicz

Every now and then a new star of the Miami art world is born. In 2025 this would be Justyna Kisielewicz (b. 1983).

In a vibrant feast for the eyes, the personal and the political collide in a recent show of paintings by this Polish-born, Miami-based artist, entitled Living Space (a calque of the uber-problematic German word Lebensraum).

In this exceptionally good painting (in CT’s opinion) depicting herself in Brobdingnagian proportions overlooking a fantastical scene traversed by a Swiss railroad, Justyna Kisielewicz (b. 1983) creates an expansive and fascinating world for viewers to discover in her exhibition, Living Space, at Miami’s Galeria La Cometa.

Having grown up in late-communist Poland and now living in tropically saturated Miami, Kisielewicz creates from a place of profound understanding of history and ideological extremes.

Her canvases are clever explorations of colonialism and its contemporary legacy: the relentless market for luxury goods. She populates these scenes with a cast of recurring characters, most notably, herself and her Pomeranian dog, turning vast historical critiques into an intimate, autobiographical mythos.

The surface is one of playful abundance, but the details reveal a sharp, critical mind. Gucci and Hermès are rendered with the same meticulous care as allusions to the enslavement that powered the original craze for luxury goods from the Caribbean, creating a unified critique of power and consumption.

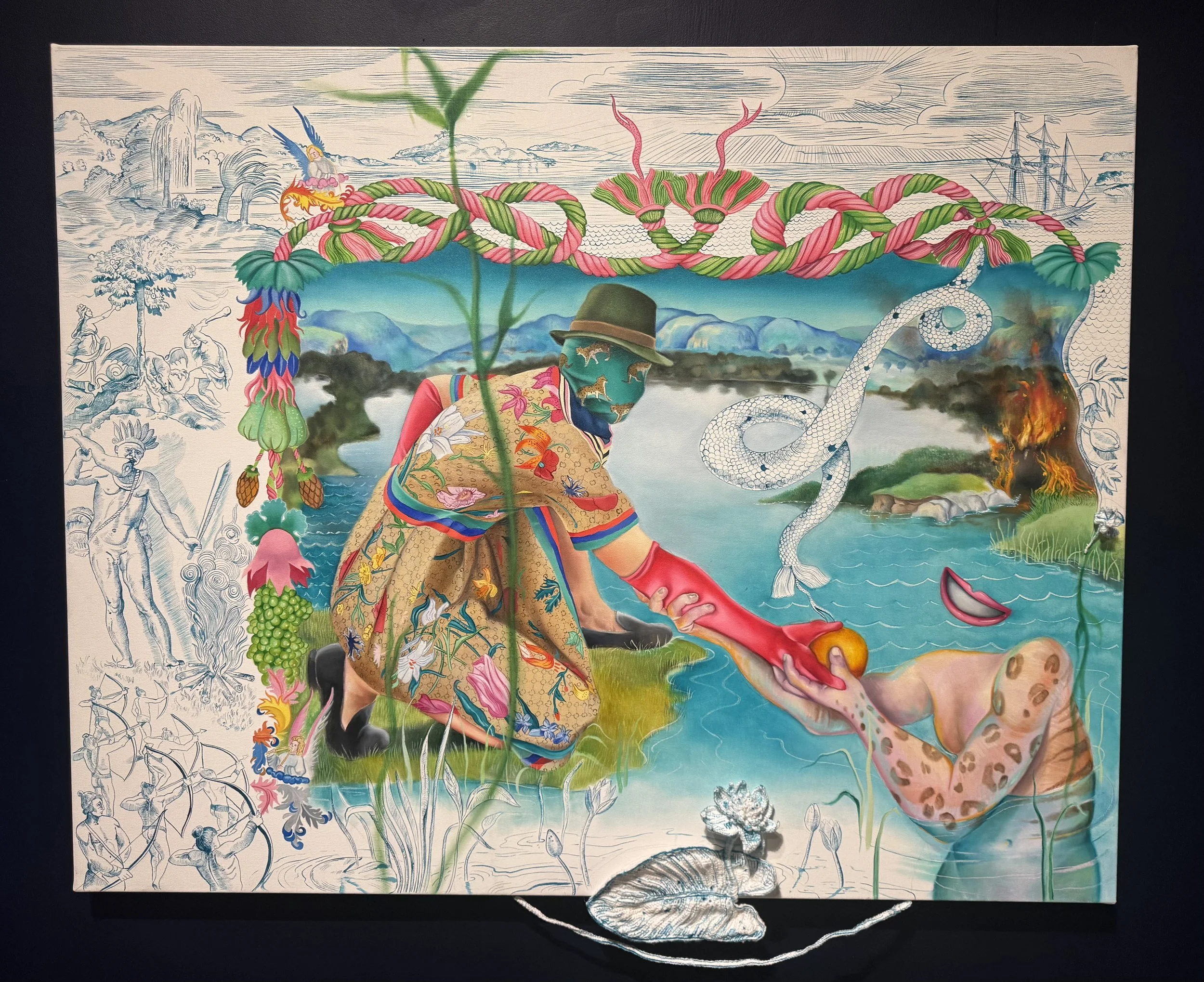

Justyna Kisielewicz, DEALINGS WITH DEVIL (2024), oil and crochet on canvas, 48” x 60,” available from Galeria La Cometa in Miami. This magnificent makes many playful (and painful) references to the luxury goods trade, colonial conquest, and the Cheshire Cat from Alice in Wonderland, among others.

This visual richness is enhanced by her integration of embroidery and crochet, adding a unique, tactile depth to the work.

For the astute art collector, the signals are clear: Kisielewicz’s work possesses the rare combination of a compelling personal story, technical innovation, and serious institutional recognition.

Indeed, my instincts as an advisor were validated when I learned that several of her best works were recently acquired by Don and Mera Rubell for their eponymous museum, arguably the best collection of contemporary art in Miami.

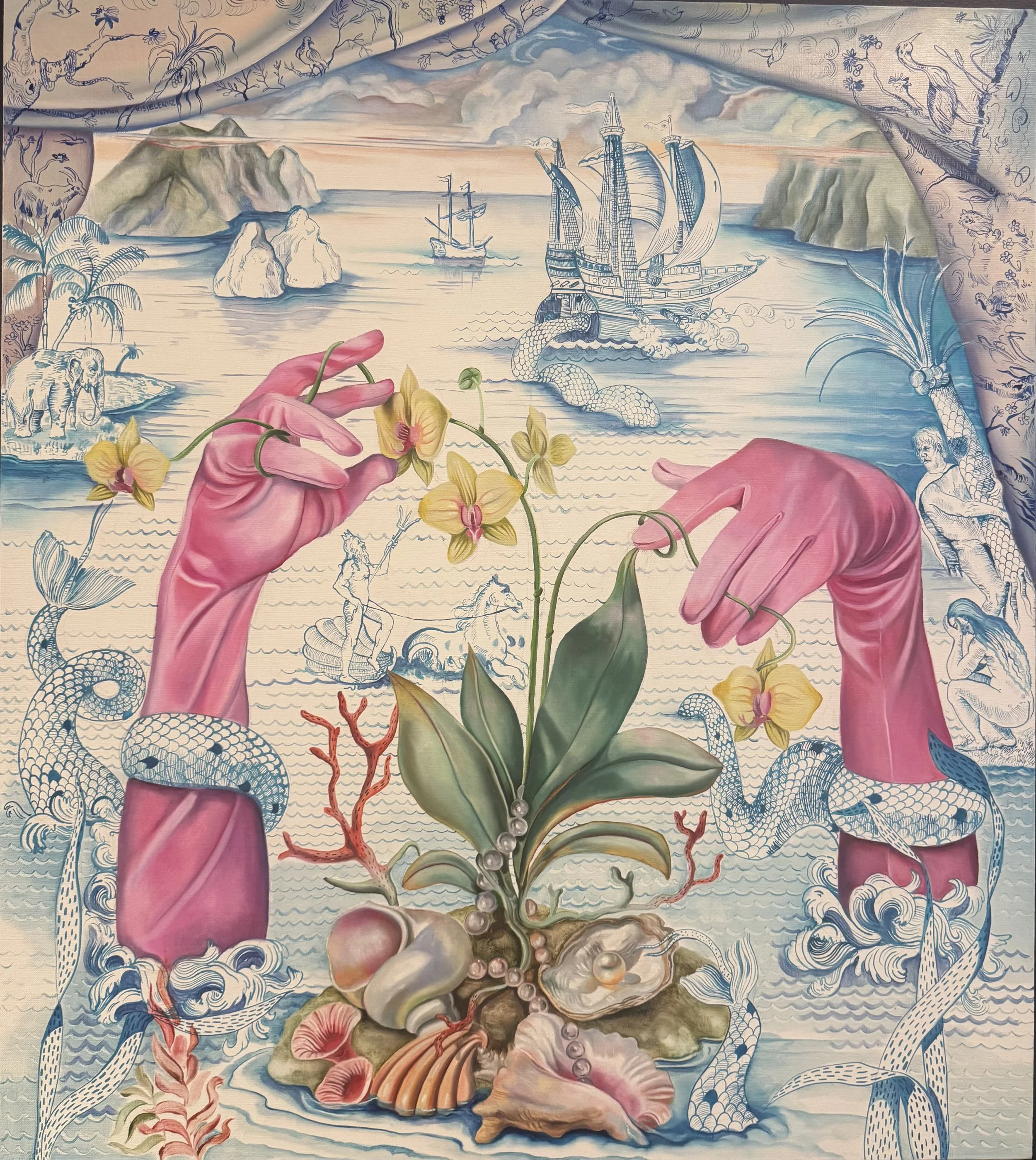

A pair of pink-gloved hands channel the tropical bounty of Miami over a suggestive ensemble of shells, pearls and orchids, flanked by intricately painted characters out of 18th century map illustrations, in this incredible canvas by Justyna Kisielewicz.

This religiously and politically satirical painting, Virgin and Child/Psia Bozia (2022), oil on Belgian linen, features the artist and her Pomeranian.

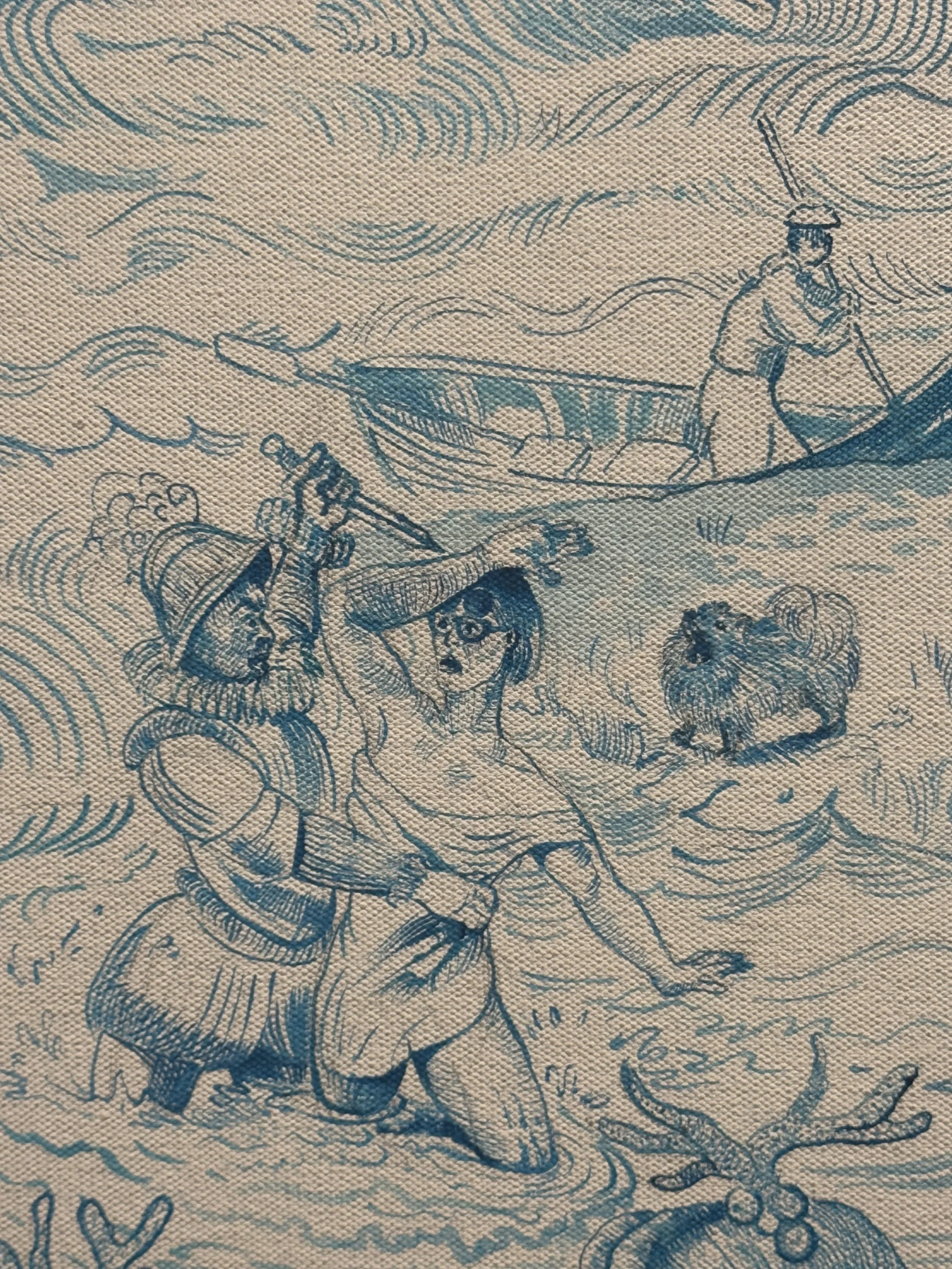

Close-up detail of Blood Lands (2024), offering appreciation for the artist’s brushwork while recounting difficult stories. Note that the dominant blue-and-white colors on Belgian linen in much of her work subtly refers to Delftware, itself a product of colonial ambition and international trade referenced in the paintings.

Skillfully blending painting with embroidery, Eastern and Western themes of landscape, seems to come naturally to Kisielewicz, making her an exceptionally promising artist to watch — among the very best emerging artists I’ve come across this year.

A Global Tour of Sculpture (From My Pocket Archive)

Compiling this fortnightly missive is a task I truly relish, but it also betrays a secret: sometimes, to keep my audience entertained, I have to go digging for some archival material.

The best place for that, typically, is my camera roll, a 15-year, pocket-sized ledger of images of art I’ve loved, captured in an instant on an iPhone while circling the globe. (Side note: I am a pretty decent photographer who trained professionally, and 99% of images I share in these newsletters are ones I’ve shot myself).

The theme for this brief interlude? A selection of just a few of the most interesting sculptures I’ve encountered around the world.

Channeling the beauty and perfection of mathematics, 11 Acute Uneven Angles (2016), is a corten steel sculpture by French artist Bernar Venet (b. 1941) at the magnificent Besthoff Sculpture Garden (one of the best in the USA in CT’s opinion) at New Orleans Museum of Art.

Diana (1947), a bronze sculpture by Paul Manship (1885-1966), in the collection of the Swope Museum of Art in Terre Haute, Indiana. Other copies of this sculpture are in public collections, including the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington and the Norton Museum of Art in West Palm Beach, Florida.

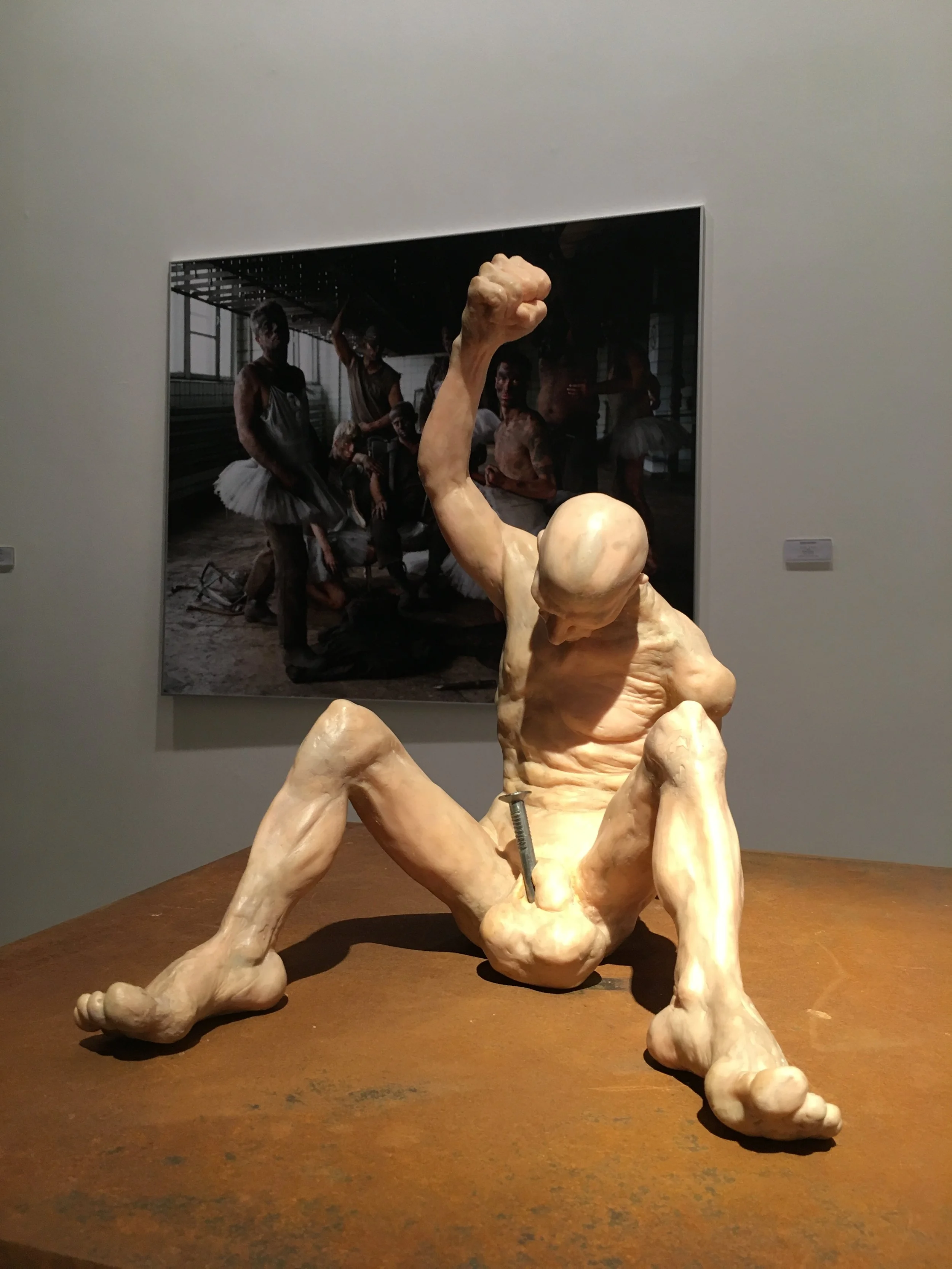

Oleg Kulik (b. 1961), The End of Revolution (2017), which I saw that year at London’s Saatchi Gallery, commemorates an important piece of performance art that took place in Moscow in 2013 when Petr Pavlensky (b. 1984) nailed his scrotum to Red Square in a politically driven artwork entitled Fixation (2013).

A magnificent TV Buddha sculpture by Nam June Paik (1932-2006) that I saw in a museum show in Shanghai in 2018 that celebrated the connections between paik and seminal German post-war conceptual artist Joseph Beuys (1921-1986).

A giant, sleeping Buddha, photographed near Vientiane, Laos, in 2015, forms part of the folk art installation Xieng Khuan (Buddha Park) near Vientiane, Laos. The sculptures appear centuries old but are actually made of reinforced concrete.

A skywards view from the base of Needle Tower II (1969) by American sculptor Kenneth Snelson (1927-2016) in the collection of the Kröller-Müller Museum in Otterloo, Netherlands.

Founded in 1978 as part of a program for rebuilding the city into a destination of love and peace, the Hiroshima Museum of Art is heavy on Western art treasures acquired during Japan’s post-war economic boom, such as this sculpture by Aristide Maillol (1861-1944).

Burn the Formwork (2017) by LA-based sculptor Oscar Tuazon (b. 1975) was a highlight of that year’s Sculpture Projects Münster (a decennial of the world’s best contemporary sculpture, held in years ending in “7”) for how its minimalist form and careful placement in a derelict corner of the city naturally attracted local youth to use it as a meeting point and fireplace.